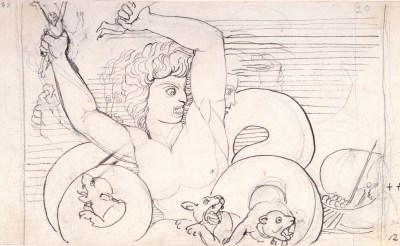

John Flaxman RA, Apollo and Marpessa, ca. 1790-94.

Marble relief. 484 mm x 548 mm x 69 mm, Weight: 43 kg. © Photo: Royal Academy of Arts, London.

This image is not available to download. To licence this image for commercial purposes, contact our Picture Library at picturelibrary@royalacademy.org.uk

Apollo and Marpessa, ca. 1790-94

John Flaxman RA (1755 - 1826)

RA Collection: Art

On free display in Collection Gallery

In this marble relief John Flaxman depicts Apollo attempting to carry away the beautiful mortal Marpessa. In Greek mythology, Marpessa, an Aetolian princess, was wooed by both the Messenian prince Idas and the god Apollo. She was carried off by Idas in her chariot but Apollo found Marpessa and Idas, and tried to take her (the moment shown here). At this point Zeus, the king of the gods, intervened, and ordered Marpessa to choose between the two. She eventually chose Idas as she was fearful that Apollo would leave her when she grew old.

In the finished work Idas is absent, the better to focus on the relationship between Apollo and Marpessa, and so departing from Flaxman’s sources. Indeed, there would be some uncertainty as to which encounter between Apollo and Marpessa was being represented here, were it not for related drawings by the artist which show Apollo removing Marpessa from the chariot of Idas. These drawings are in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (reproduced Irwin, p.171, fig.234) and the National Galleries of Scotland (inscribed ‘Apollodorus’ lower right, indicating Flaxman’s literary source). The absence of Idas in this sculpture shifts it from a literal rendering of the narrative to a more romantic scene.

Flaxman carved this sculpture in Rome, where he lived and worked between 1787 and 1794. It reflects the influences Flaxman absorbed in Italy, from Greek vase painting (which he admired for its linear rhythms and economical design) to the highly-finished surface popular amongst Italian sculptors. It has been suggested that Flaxman may have received assistance from Italian studio assistants to produce this finish.

Apollo and Marpessa was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1800 and presented by Flaxman as his Diploma Work the same year. Flaxman’s decision to submit a bas-relief as his Diploma Work was in keeping with that of other sculptor Members at this time including Joseph Nollekens, Sir Richard Westmacott and Richard Westmacott the younger. It has been suggested that this was because they could be exhibited alongside paintings and so were easier to display.

The work demonstrates how Flaxman successfully translated the classical line of his celebrated illustrations to Homer (which also date from his time in Italy) into sculptural form. Flaxman felt he could only ‘convert the beauty and grace of ancient poetry’ by composing ‘the grand lines of figures without the intrusion of useless, impertinent or trivial objects’. (Flaxman, Lectures, p.232). Accordingly in this sculpture only a delicate sprig of ivy trailing across the outline of a column, and rocky ground beneath Apollo’s feet, situate the scene in physical space.

Apollo and Marpessa also highlights the importance Flaxman gave to drapery in a composition. He believed that drapery was ‘a medium through which the human figure is intelligible’ and that by creating ‘those gentle and harmonious undulations’ figures acquire grace and dignity (Flaxman, Lectures, p.195). Marpessa’s drapery is balanced by Apollo’s cloak, which billows out behind him. The figure of Marpessa is in unusually high relief for Flaxman, particularly the fall of the drapery on her leg.

Further Reading

Katherine Eustace, ‘John Flaxman: Apollo and Marpessa’ in Robin Simon and MaryAnne Stevens (eds.), The Royal Academy of Arts: History and Collections, London and New Haven, 2018, pp.210-211

John Flaxman, Lectures on Sculpture, 1838

David Irwin, John Flaxman 1755-1826. Sculptor, Illustrator, Designer, London, 1979, pp. 169-171

Michael Simpson, trans., Gods and Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, Amherst, Mass., 1976

Marjorie Trusted, The Return of the Gods, Tate exh. cat., 2008, p.24

Object details

484 mm x 548 mm x 69 mm, Weight: 43 kg

Start exploring the RA Collection

- Explore art works, paint-smeared palettes, scribbled letters and more...

- Artists and architects have run the RA for 250 years.

Our Collection is a record of them.