Sir Thomas Lawrence PRA, Satan summoning his Legions, 1796-1797.

Oil on canvas. 4318 mm x 2743 mm. © Photo: Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photographer: Marcus Leith.

This image is not available to download. To licence this image for commercial purposes, contact our Picture Library at picturelibrary@royalacademy.org.uk

Sir Thomas Lawrence PRA, Satan summoning his Legions, 1796-1797.

Oil on canvas. 4318 mm x 2743 mm. © Photo: Royal Academy of Arts, London.

This image is not available to download. To licence this image for commercial purposes, contact our Picture Library at picturelibrary@royalacademy.org.uk

Satan summoning his Legions, 1796-1797

Sir Thomas Lawrence PRA (1769 - 1830)

RA Collection: Art

Thomas Lawrence’s grandest history painting attracted strong reactions. It is dominated by a muscular male figure, naked apart from his sword, helmet and some carefully placed drapery. He is Satan, the rebel angel, who has been sent to Hell. Standing by a lake of fire, he summons his followers. The subject is Milton's ‘Paradise Lost’, Book I, line 330, 'Awake, arise, or be for ever fallen'.

Lawrence made a bold decision to paint this imposing painting for the 1797 Royal Academy Annual Exhibition, where it was titled ‘Satan calling his Legions. First Book of Milton’. It attracted attention and criticism at the exhibition and even before it was finished, when people saw it in Lawrence’s studio. The painter Richard Westall RA was sceptical about it, stating he ‘did not think Lawrence qualified to paint Historical subjects. He has little of the creative power.’ (Joseph Farington’s Diary 12 April 1797) During the installation of the exhibition John Hoppner RA said he ‘wd. Give £100 to have Lawrences Satan out of room, as it takes effect from his pictures.’ (Joseph Farington’s Diary 25 April 1797) In 1830 the painting was exhibited at the British Institution with the line from Milton as its title, 'Satan! - Awake, arise, or be for ever fallen!'

Competition with Fuseli

Lawrence’s Satan was seen at the time, and since, as being very close to, even deliberately competitive with, some of the work of Henry Fuseli RA. Joseph Farington reported 'Fuseli considers Lawrence having taken up a subject from Milton as something like opposition to him.’ (Joseph Farington’s Diary, 12 April 1797) The RA Annual Exhibition opened to the public on 1 May 1797. That day, Fuseli wrote that, perhaps to upstage Lawrence, he was planning a 14-feet high picture of ‘Satan on the flood’ and in that context he wrote of Lawrence’s Satan, ‘what the Exhibition Shews to oppose me, I have seen, and I am confident that my Rival in this work is Yet to Come.’ Fuseli is also reported by the Redgraves to have described Lawrence’s Satan as ‘a damned thing certainly, but not the devil.’ (David H Weinglass, The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli, 1982, p167)

Possible meanings

David Bindman does not discuss Lawrence’s picture specifically, but suggests that for English artists in the 1790s, Satan’s ‘heroic defiance of the Almighty could be taken as a model of resistance to a distant and arbitrary power… The French Revolution, especially as it passed beyond the stage when English radicals could regard it as a new dawn for humanity, began to appear even more Miltonic, as destruction, chaos and envy seemed to attend it, as they did Satan on his travels across the universe. Milton could be seen, depending on one’s degree of revolutionary commitment, as a prophet of Revolution, who had foreseen its inevitable collapse into tyranny, or alternatively had witnessed its hard and painful progress before it could achieve its aims.’ (David Bindman, The Shadow of the Guillotine, Britain and the French Revolution, exh cat, British Museum Publications, 1989, p166)

Michael Levey instead prefers a contextualisation based on Lawrence’s childhood interest in Paradise Lost ‘which can be said from childhood to have haunted Lawrence’. Levey saw the painting before it was conserved, ‘No amount of darkened varnish and discoloured paint can conceal the imperious pose of Satan’s naked, muscular figure, with arms upraised and eyes glaring out from a helmeted head. The rest of the composition must always have been shadowy, intentionally subordinated to that single form.’ (Levey 2005, p129)

Critical responses

The painting has a reputation for being a critical failure. The outspoken critic and satirist Anthony Pasquin wrote:

‘The frequency with which we have been annually compelled to notice the daring folly of our callous Artistes, in assuming the baton of an historical Painter, before they had even a common knowledge of the human anatomy, has filled us with regret, yet it appears, that no warning can refrain their lunacy, nor any admonition amend their manners:- before Michel Angelo, or Rafaelle, attempted to walk in this path of sublimity, they added the force of incalculable and unremitting study to the purest and strongest endowments, and even then they took up the pencil tremblingly, well knowing the complicated difficulties of the pursuit. "But fools rush in, when angels fear to tread." The picture is a melange, made up of the worst parts of the divine Bonarotti [ie Michelangelo], and the extravagant Goltzius: the figure of Satan is colossal and very ill drawn: the body is so disproportioned to the extremities, that it appears all legs and arms, and might, at a distance, be mistaken for a sign of the spread eagle. The colouring has little analogy to truth as the contour, for it is so ordered that it conveys an idea of a mad German baker, dancing naked in a conflagration of his own treacle! (A.P. [Anthony Pasquin] Royal Academy. Twenty-Ninth Exhibition, [1797] In Royal Academy Critiques, Vol. II, p10)

However, other critics were more positive, if negative about some details:

‘The artist has evinced his exertion of powers in this picture to the extent of poetic enthusiasm highly descriptive of a vigorous mind and excentric [sic] imagination. But in such moments of impassioned energies, there is the greatest danger of carrying genius to the verge of extravagance and indecorous representation. With out any desire to check the ardour of a warm fancy, the following caution is submitted to Mr. Lawrence. In all designs for public exhibition, a regard should be paid to the morals of the spectators… Female delicacy must be shocked at such a monstrous display of the human form as an entire nudity except where the sword is girted [sic] to the thigh. But with respect to the picture, it has certainly much transcendent merit. The character is sublimely impressive of a mind devoted to the horrors of mischief. The attitude is grand, sublime, and terrific… One of the greatest beauties in the whole picture is the tone of dismal glare diffused over the body of Satan contrasted with the gloom in which he is, otherwise, enveloped… It must, however, be observed that the light on the eye-brows being too strong, and not so judiciously managed as it might have been, gives an appearance of two pieces of transparent horn instead of eye-brows. Some few defects in muscular expression are also visible. But these are "trifles light as air" when weighed in the balance of all the excellences of this extraordinary performance.’ (A Companion to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy, containing Critical Sketches of the Principal Paintings with a Key to the Portraits, London, 1797, pp21-23. In Royal Academy Critiques, Vol. II)

The strong, often negative reactions to the picture from artists and critics meant ‘Lawrence never again attempted a completely imaginative composition.’ (Levey 2005, p130) ‘He never displayed any ability to execute the non-portrait compositions of which he dreamed. Satan Summoning his Legions may have been unfairly stigmatised at the time, though it… lacks the effortless originality of several major portraits he had previously painted… Haunted doubtless by the example of Reynolds, himself managing only fitfully to escape the shackles of portrait painting.’ (Levey 2005, p11)

Fourteen years after painting Satan, Lawrence expressed pride in it, and wished he had devoted more of his time to history painting. On 29 October 1811 he wrote to Joseph Farington: ‘I have been out with Lord Mountjoy… to show him my Satan… and I am returned most heavily depressed in spirit from the strong impression of the past dreadful waste of time and improvidence of my Life and Talent. I have seen my own Picture with the eye of a spectator – of a stranger – and I do know that it is such as neither Mr West, not Sir Joshua, nor Fuseli could have painted. I will request you to go with me and confirm this judgment.’ (Lawrence letter RA/1/289; published in G. S. Layard, Sir Thomas Lawrence's Letter-Bag, George Allen: London, 1906, p84)

Celebrity Models for the Figures?

There is an often repeated tradition that the model for Satan's body was boxer John Jackson, the face was based on the actor John Philip Kemble (brother of the actor Sarah Siddons) and the figure hidden in smoke at Satan's feet is based on Sarah Siddons herself. The evidence for this appears anecdotal, perhaps in part originating from Williams who says an 'uncommonly powerful man' who was a childhood friend of Lawrence was the model for Satan (D.E. Williams, Lawrence, 1831, vol. I, pp16-17) and Whitley, who says 'the youthful Fanny Kemble... fancied that she could trace in its fierce and tragical expression some likeness to her uncle and aunt, John Philip Kemble and Mrs Siddons.' (William T. Whitley, Art in England, 1821-1837, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1930, p326). By the 1950s the entire tale of Jackson, Kemble and Siddons being models is presented as fact in Douglas Goldring, Regency Portrait Painter, 1951, p110.

Lawrence did seek Siddons’s views, on the painting, ‘I have consulted her and her brother on my picture of Milton... I had projected a material alteration in the action of my figure, and asked his opinion of it. He… told me, “it was not natural.” I asked Mrs Siddons, if she agreed in his decision? “Certainly,” she said, “if in painting from Milton it is the natural you look for.”’ (West, 2012, p3)

Related works

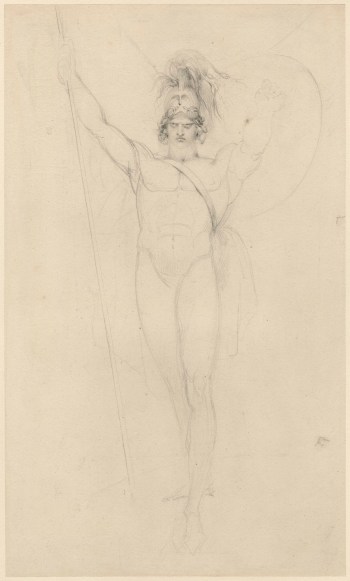

The RA Collection includes a preparatory drawing.

There are up to eight related drawings by Lawrence recorded (K. Garlick, Walpole Society, XXXIX, 1964, p255).

Other artists produced comparable images of Satan: JR Cozens's Satan Summoning his Legions c1776 (watercolour, Tate, T08231), James Barry’s Satan and his Legions Hurling Defiance toward the Vault of Heaven c1792-5 (drawing in British Museum and etching) and Richard Westall’s Satan Summoning his Legions, 1794 (stipple engraving) all show Satan with arms raised (only one arm raised in the case of Cozens) holding a staff and legs wide, in rather similar poses to Lawrence’s version. Fuseli also depicts Satan with legs astride and arms raised (although not holding a staff) in Satan Calling up His Legions, 1802 (Kunsthaus Zurich).

Further reading

Michael Levey, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Yale University Press, 2005

National Portrait Gallery and Yale Centre for British Art, Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power and Brilliance, exh cat, 2010, pp90, 149, 152

Shearer West, The Professional and Personal Worlds of Artists and Actors: Thomas Lawrence and the Siddons Family, Nineteenth Century Theatre & Film, 2012, Volume 39, Number 1, p3)

Object details

4318 mm x 2743 mm

Associated works of art

2 results

Start exploring the RA Collection

- Explore art works, paint-smeared palettes, scribbled letters and more...

- Artists and architects have run the RA for 250 years.

Our Collection is a record of them.