Art and activism: can it change the world?

By Jen Harvie

Published on 20 October 2015

Performance and protest is key to the work of Ai Weiwei, as it is to many of his contemporaries. But in the face of global crisis, can art really effect change? Professor Jen Harvie explores the role of the artist-activist.

Walking for refugees

Two days before the mid-September opening of his Royal Academy exhibition and weeks after being permitted to travel outside China for the first time since 2011, Ai Weiwei and Anish Kapoor walked east together from central London to Kapoor’s 2012 sculpture, Orbit, in Stratford. A focus of their walk was London’s East End, home to centuries of immigrants fleeing oppression and deprivation, including Jews, French Huguenots, Irish, and Bangladeshis. Both artists carried a blanket to indicate fundamental human rights to rest and security. They have said they will walk together again in other cities.

In the months before this walk, the refugee crisis had become a catastrophe, with thousands of desperate Middle Eastern and African migrants pushing on Europe’s frontiers and hundreds drowning or being assailed by water canons and tear gas. Governments across the world failed dismally to prevent the unfolding disaster. Ai and Kapoor walked to draw attention to the need for a coordinated, global, proportionate humanitarian response to this worldwide refugee crisis.

Imagining change

We might ask how a performative gesture such as a walk can even begin to make an impact on the crisis when what is needed is so much more, encompassing transnational policy, legislation, governmental coordination, funding, and myriads of other resources. What on earth can a walk do?

If you can imagine it, you can make it; if you can make it, you can make it change.

Lois Weaver

The walk performs the possibility of freedom of movement; Ai and Kapoor’s blankets perform security. Like other performative activist actions, the walk imagines and models change. It is a synecdoche: a part – a pair of men walking – stands in for a global whole – the entire world making constructive change.

In another series of performative art works, Ai and others responded to Sichuan’s May 2008 earthquake and the Chinese government’s efforts to conceal its death toll and preventable causes. Many citizens took part in the "Citizen’s Investigation" to uncover names of those killed. Their "singular" actions became collective; many people ultimately compiled the over 5000 names that are now memorialised on the walls of the Royal Academy galleries (exhibited alongside Ai's huge Straight installation, see below).

Performative art cannot provide all necessary means of making change. It cannot solve the refugee crisis or bring back Sichuan’s dead. But it can provide catalyst for change. By showing action is possible, it can foster belief that change is possible. Perhaps art provides change’s most important ingredient: imagination. As feminist performance maker Lois Weaver says, if you can imagine it, you can make it; if you can make it, you can make it change.

What art and performance can do for activism

Thinking about such artistic works as performance supports understanding how it functions so powerfully. The character or persona commands attention. The American artist-activist Reverend Billy channels ebullient televangelist powers into persuading people to be less consumerist. Like Billy, Ai is mischievous and dissenting. He sticks his middle finger up at the White House and Tiananmen Square (Study of Perspective, 1995-2011).

Unlike Billy, Ai performs with a commanding, ruthless stoicism. The sure-footed stance and implacable gaze of Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) convey stoicism. Ruthlessness – or steadfastness – is expressed by unrelenting follow-through. Every minute detail of his jailing for almost three months in 2011 is recreated in the miniature cells of S.A.C.R.E.D. (2011-2013). Following his release, every day until his passport was returned to him earlier this year, the artist had fresh flowers placed in the bicycle basket outside his studio in protest. Ai’s dissenting, stoical, steadfast persona commands attention and inspires admiration, sympathy and imitation.

It’s also informative to think of Ai’s work as performance in ways it uses space. Location matters, be it the East End of Ai and Kapoor’s walk, or the interior of Ai’s cell. Spatial relations matter; S.A.C.R.E.D. requires audiences to adopt perspectives of surveillance. Ai’s work with space takes us there. It implicates us in spatial power dynamics and provokes us to take responsibility for complicity with them.

Activism emotionally enhanced

Performative art work exploits many more elements of performance which signify powerfully – time, props, scenographies, texts, and soundscapes. Perhaps most importantly, all these performative features provoke feeling. The time taken to collect and render thousands of rebars in Straight is like a period of mourning. The 9000 children’s backpacks of Remembering (2009) signify as what they are but also what they stand in for – children needlessly killed.

Performative activism imagines change. It provokes feeling, be that sympathy, anger, or love. Its affective force compels us to pay attention, and sometimes to copy it, however we can.

S.A.C.R.E.D., 2011-2013

Ai's work S.A.C.R.E.D. reflects upon his time in detention. It takes the form of six iron cuboids, which will stand in the RA gallery at shoulder height. Through apertures in the metal façade of each cuboid, visitors will be able to peer inside and view miniature dioramas of Ai's imprisonment, the artist and his guards replicated in fibreglass

Remembering, 2009

Displayed outside the So Sorry exhibition at Haus der Kunst, Munich

Straight, 2008–2012

Further reading

Explore a few other examples of artists working with activism and performance:

• Michael Landy and his counter-consumerist Break Down (2001).

• Platform and Art Not Oil’s advocacy against arts organisations accepting funding from petroleum companies.

• Francis Alÿs’s walks with leaking paint cans on contested borders.

• Oreet Ashery’s parties for freedom.

• American Kara Walker’s stagings of racial violence.

• Work documented at the Live Art Development Agency.

Jen Harvie is a Professor of Contemporary Theatre and Performance. She leads our roundtable event, Performance of the artist on Saturday 17 October.

Related articles

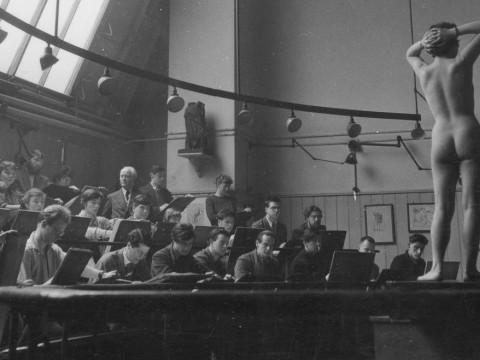

Victorian women and the fight for arts training

2 March 2021

Eight of the best home art activities for kids

19 January 2021