Why TV-am was Britain's most maverick building

By Adam Nathaniel Furman

Published on 29 April 2016

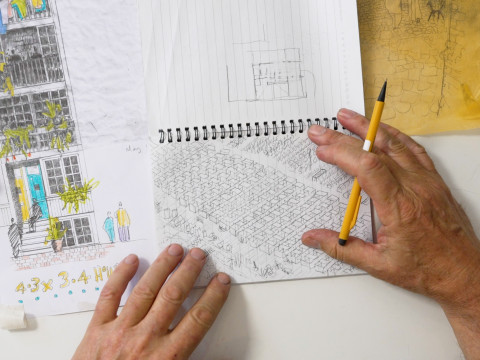

Home to ITV's famous breakfast show, Terry Farrell's postmodern studio was a burst of energy that shifted views of what architecture could be, says the artist and designer, Adam Nathaniel Furman.

By the early 80s, architect Terry Farrell was looking for any and every opportunity to break out. He had separated from the partner with whom he'd worked for 15 years, Nicholas Grimshaw – a devotee of the High Tech movement (and also incidentally a former President of the RA). Farrell had just authored the iconic Clifton Nurseries, as well as the private wonderland of the Thematic House in Holland Park for Charles Jencks. But it was his pairing with a media company in 1981, with the idea of an architecture that embodied the new media age, that was to provide him with the fuel to definitively blast out of the orbit of anything that might have been even vaguely recognised as “proper”, let alone “modern”, architecture.

TV-am was a building of the media, for the media. The home of the first national operator of a commercial breakfast television franchise, broadcast on ITV, it intentionally heralded the beginnings of our now dizzyingly saturated era with its palatially cheap-and-cheerful exuberance. As Terry explains, he “was very keen on the idea that television created a virtual existence," seeing "it as an opportunity to create a representation of the TV channel through a building."

It was a complex, clever, and delightfully giddy stage-set, back-drop, and active instigator in the nation’s newfound commercialised breakfast pleasures. Mad Lizzie and her team did aerobics under the neon sunrise keystones of the its retro-futuristic-classical-pop entrance arch, while its oh-so-eloquent plastic eggcup finials were beamed straight into our living rooms as the utterly endearing markers of the end of each morning’s entertainment, as well – of course – as being reminders of the classical canon, of the egg-and-dart motif.

This was a building done on an incredibly tight budget (it was in fact one of the cheapest studio complexes ever built), and to a fast-track program, and the client saw the eggs as an unnecessary excess, forcing Farrell and his team to pay £100 per egg themselves, thereby funding what turned out to become the most recognisable icons for the company nationwide, out of their own pockets.

...topped by the famous ornamental eggs

The TV-am building has since been extensively renovated – but its signature eggcups remain visible on the facade facing Regent's Canal.

...says artist and architect, Adam Nathaniel Furman

But really the whole building, inside and out became the very image of the brash new television station. Its interior was like the absolute coolest American industrial design and Italian fashion had exploded on impact with the dour British working environment, performing with perfect ease as the backdrop for impromptu broadcasts, being far more interesting than the majority of the actual TV-show sets themselves.

The wild contrast between the various parts of the building was purposefully cultivated during the design process through a technique that Farrell borrowed from his brush with High Tech. The project was divided into four competing and distinct teams with their own leads, the front facade led by Simon Sturgis, back facade led by John Letherland, and all interiors led by Clive Wilkinson – meaning that each part competitively developed entirely distinct characteristics. The eggcups to the rear, the sunrise arch to the front, and the ziggurat, Japanese Temple, reception desks and furniture inside.

TV-am was a Pop building, through its sheer abundance of metaphor – which although it did reference historical precedent, was far more about communicating with those not indoctrinated in architecture – it broke the idea that Postmodernism was an esoteric, historicist, elitist movement. Farrell describes the project as a "tremendous release", and it was, a huge burst of energy that altered perceptions of what architecture was allowed to do, and be.

TV-am was a rapturous celebration of its contents – a building that functioned perfectly as a studio, but which also performed brilliantly as a story about the new world we were entering

Adam Nathaniel Furman

Buildings, spaces, tools and machines of high-tech media content, whether it be smartphones or studio buildings, are today mostly the very inverse of that which they contain and produce – they are all too often black boxes, slick tablets and neutral sheds.

TV-am was something it would be wonderful to see more of: a rapturous celebration of its contents, a building that functioned perfectly as a studio, but which also performed brilliantly as an architectural embodiment of, and story about the new world we were entering, in which old categories were dissolving and hierarchies collapsing, in which cleverness could be a joy, old could be new, pop could be culture, and architecture could be free to be sophisticated, fun, fashionable and communicative. It was a stylistic explosion of pent-up tectonic energies that formed itself around the volatile excitement of a new media age, and in the process became entrenched in our national consciousness.

As Paul Greenhalgh said, postmodernism stands in relation to our own moment as the Steam Age did to its own oil-powered future; the mediated nature of our economy and lifestyle that was only beginning with TV-am has now effloresced into a saturated environment unimaginable at that time.

TV-am encapsulated the complexities of its era – good and ill, beautiful and ugly – with stylistic bravado and architectural panache. Embodying the excitement of our hyperreal and mediated world is something that architecture does with exceptional rarity, and never – that I know of – with the vivacious clarity of shown at TV-am, making it a truly great, British Maverick.

It would be very good indeed to see young architects pick up this baton, and throw themselves headlong into the maelstrom of contemporary culture, bringing some of its raw brilliance back into the built environment. In its Maverick spirit, it is actually a model extremely relevant to today that should be revaluated, revisited and taken-up once again.

Adam Nathaniel Furman is an artist and designer. He championed the TV-am building at our recent debate and won the vote to crown it Britain's most maverick building.