A beginner's guide to Milton Avery

Published on 11 July 2022

Don’t know Milton Avery? Here’s our handy guide to the visionary artist who influenced Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko.

He was a master of colour

Artists and critics alike have lauded Avery's employment and application of colour on canvas.

In 1952 the revered artist-teacher Hans Hofmann said that: “Avery was one of the first to understand colour as a creative means. He was one of the first to relate colours in a plastic way.”

From his early Impressionist landscapes to his later paintings of bright, flattened forms, Avery's career is marked by a brilliant intuition for colour.

He was a factory worker before he was an artist

Born in 1885 into a working-class family in Connecticut, Milton Avery's path to being a painter wasn't clear cut. He left school at 16 and spent a decade working in different factory jobs as an aligner, an assembler, a latheman and a mechanic.

In 1905, Avery took the first step towards becoming an artist when he enrolled in a night class in commercial lettering in Connecticut. Luckily, his tutor advised him to switch to life drawing classes instead.

Thus began 15 years of artistic training in New England. Avery was a dedicated art student, and from 1915 he began appearing in exhibitions where his work was often celebrated – after one exhibition in 1919, a fellow artist said: "Mr Avery used a brush and a canvas to write poetry".

His wife was his greatest supporter

In 1924, Avery met Sally Michel, a much younger artist, and the pair married and moved to New York City. They were a happy and supportive couple who got by on a meagre living.

With her strong belief in her husband’s artistic abilities, Sally determined to support them both by taking on commercial-drawing work, which enabled Avery to continue to concentrate solely on his painting for the remainder of his life.

Sally also sat for her husband; according to Mark Rothko, Milton Avery’s "repertoire" of subjects was "His living room, Central Park, his wife Sally, his daughter [March]… his friends and whatever world strayed through his studio”.

He didn't follow rules

“I never have any rules to follow… I follow myself”

The period in which Avery worked straddled American Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism, and while he learned from and responded to both movements, he never followed or committed to either. Instead, he constantly strove to forge his own path.

In the late 1920s, Avery abandoned the active surface, Impressionist brushwork and New England’s blue-green palette, favouring broader, flat, thinly painted areas of close-valued darker hues with occasional pops of accent colour.

Avery said of his work: “I like to seize one sharp instant in nature, imprison it by means of ordered shapes and space relationships to convey the ecstasy of the moment. To this end I eliminate and simplify, leaving nothing but color and pattern.”

He was friends with Mark Rothko

Despite the Wall Street Crash of 1929 plunging the US into a decade-long depression (Avery briefly worked on the New Deal programme for unemployed artists before his pride got the better of him), the cultural life of New York city was burgeoning in the late 1920s.

1929 saw the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art, which immediately started to programme exhibitions of international art.

In 1928 Avery’s work was selected as part of a group exhibition at the new Opportunity Gallery that included the work of a younger artist, Mark Rothko. This marked the beginning of their friendship. Through Rothko, Avery met Adolph Gottlieb the following year and later Barnett Newman, with all becoming close and admiring friends.

He was fiercely committed to his work

Avery worked quickly and his output was enormous – in 1944 alone he produced 100 oil paintings. His wife Sally said he was constantly thinking about the next painting, so by the time he began to work directly on the canvas, he already had a clear sense of the direction he wanted to take. His aim was to recreate moments he had witnessed and recorded.

Remarkably, Avery didn't work from a studio but his own home; his daughter March recalls that “he was always painting in the living room[...] He would get up, have breakfast – coffee and an English muffin – and get to work. At noon, break for lunch. He would then paint in the afternoon until about 5 pm. He used to sit down and have a cigarette when he was getting ready to paint.” March said her father approached painting "like a factory worker" and that he never had artists' block, always managing to finish a painting in a day.

He had a pet dog called Picasso

Avery likely admired Pablo Picasso's work – their paintings were hung alongisde each other in several shows, and Avery once perused his gallerist's collection of 150 Picasso works. But Picasso's influence over Avery is most obvious in Avery having a black cocker spaniel named after the Spanish artist.

March Avery recalls her father was "very patient with [Picasso] and taught him a lot of tricks – lie down, roll over, play dead. He was a very elegant dog." According to March, when important gallery owners (called the "Millionaire's Club" by the family!) would come to look at her father's work, "Picasso would walk all over the works and it was fine – until they bought them! Then they didn’t want the dog to walk on them."

He had a reputation for reticence

Avery left us with countless beautiful paintings but very little written material on his creative process and ideas. Indeed, even socially, he was reportedly a quiet man.

Avery's daughter March recalls that days would go by without her father speaking a word (which would infuriate her mother!). Apparently Avery once said “Why talk when you can paint?”

But Avery loved to socialise, hosting parties with Sally at their apartment and entertaining a host of devoted younger artists including Rothko and Gottlieb. March adds that "People who knew him tell me that he would wait for the right moment and then say the funniest or most direct things in a single sentence. And then go back to not saying anything....Maybe he didn’t have much to say. He said it all on canvas."

He painted outdoors

For five decades Avery depicted the natural world, and increasingly in the process he omitted detail, distorted form and employed non-associative colours.

Even when living in bustling New York, cityscapes didn't interest him and instead he returned to the scenery of his early days with family holidays to Connecticut where he produced huge volumes of sketches.

Avery often drew and painted outdoors, and had done so since his student days, when he carried small canvases with him into the countryside or to the seaside, painting en plein air in the late nineteenth-century manner.

He found mainstream success in his 60s

It was not until 1952, and at the age of 67, that Avery received his first full-scale retrospective museum exhibition. Opening at the Baltimore Museum of Art, this large display of 85 works travelled in a reduced form to further venues in Washington DC, Hartford, and Boston.

This exhibition gave Avery a level of national exposure he had not yet experienced, despite having been active for nearly 40 years.

Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in collaboration with The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

Get tickets to Milton Avery: American Colourist

Milton Avery expressed his vision of the world through harmonious colour and simplified forms.

Now, for the first time, see the North American painter’s work this side of the Atlantic. Bringing together a selection of around 70 paintings from the 1930s – 1960s that are among his most celebrated, this is the first comprehensive exhibition of Avery’s work in Europe.

Related articles

A beginner's guide to William Kentridge

19 July 2022

10 novels about art you won't put down

10 June 2022

Introducing our 2023 exhibitions

24 May 2022

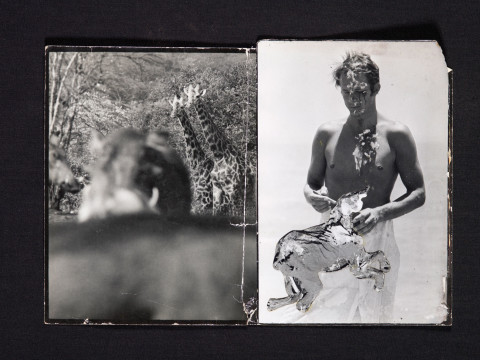

On safari with Francis Bacon

1 April 2022

Kawanabe Kyōsai: the demon with a brush

2 March 2022