Grace Woodward: can a feminist love Allen Jones?

By Grace Woodward

Published on 17 November 2014

The presenter, fashion commentator, stylist and feminist explains why she identifies with Allen Jones's controversial works and picks a few of her favourites.

As a feminist, you might think I’d hate Allen Jones’s work. Today’s women are bombarded with insipid, obvious images of what they should look and act like (usually thin, white, tall). And yet in Jones's women I see complexity, power-play and consumption mixed with desire – for me, somewhat how it feels to be a modern woman. I look at Desire Me and I think “yeah, that could be me,” and that’s rare.

Having worked in and around fashion for 15 years, Jones’s work is so familiar to me that it’s like looking at fashion as art. With the new Kate Moss works we are now playing a game of chicken and egg – I see Jones in Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin and contemporary fashion photographers such as Mert Alas & Marcus Piggott and Emma Summerton in pieces like Light Green, and now Jones himself has gone full circle with this show. As a TV producer once said to me, “Moss could piss on a piece of paper and we would want it.”

Alexander (Lee) McQueen reportedly owned some of Jones’s work in his private collection and, as Jones references were thrown around again with the latest Spring/Summer ’15 McQueen catwalk show designed by Sarah Burton, I’ve chosen To be or Not to Be (2014) – a mannequin in motion. Both McQueen and Jones have been accused of being misogynists (and the parallel between the wild consumption of Christian Louboutin shoes and Jones’s Secretary, three sets of mannequin legs, should be mentioned here) but it seems that modern female consumers, and even Burton directing them, must have Stockholm Syndrome. You wouldn’t become a slave to it if you didn’t love it.

Light Green, 2002

To be or not to be, 2014

Refrigerator, 2002

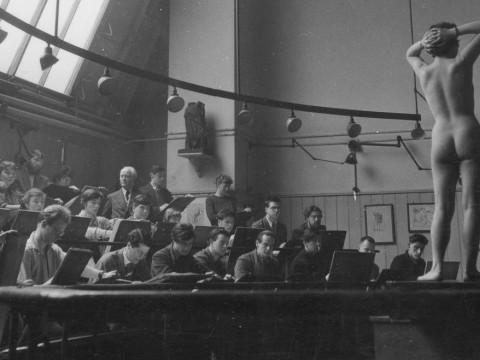

Which brings me on to Table (1969); I don’t see this as a woman being objectified. If she were nude, as in most classical art: draped, appealing, "beautiful" and always available, that’s an object. Personally, I find this traditional, submissive image less of a positive female representation than Jones’s. With the inclusion of very specific fetish attire in Table, as in S&M, this reflects to me that the woman has chosen the role. It doesn’t offend me that a man made the piece either. If a woman had made it, would it automatically make her a feminist? If only women’s view of one another was as simple as objectification. The ultimate feminist statement for me would be to be successful enough to own it, not destroy it. Can you tell I grew up under Thatcher?

Another Jones work I admire is Refrigerator (2002). I was only disappointed that the cold hearted femme wasn’t actually serving up the poison of your choice in the show. Jones’s work makes me want to consume that lifestyle, the glamorous one of style and cocktails that we see endlessly fantasised on pages of fashion magazines. Having met the editors of glossy women’s fashion magazines, I find Refrigerator refreshingly on point.

Jones’s work to me is like the phenomenon that is Topshop. It’s bright, hard, full of Kate Moss and you kind of know that somewhere, something dark is going on. But most women can’t help but wonder if there’s something in there for them.

Allen Jones RA is at 6 Burlington Gardens at the RA until 25 January 2015.

Grace Woodward is a presenter, fashion commentator and stylist. She joins curator Edith Devaney, Stacy Boldrick and Lyndsey Morgan for an intimate salon exploring Allen Jones’s controversial work Chair on Friday 5 December. Book here.